Why Tarsila do Amaral Became an Icon in Brazilian Art History

What comes to your mind when you think of historical artists who pioneered modern art?

Definitely not Tarsila do Amaral, the woman who said, “I want to be the painter of my country,” and actually became the painter of her country.

Tarsila is the exact definition of the word “exceptional.” From her paintings to the movement she inspired, Tarsila didn’t do what others did.

Born from a wealthy background, you would expect her to follow a more refined career path, or maybe just do what women in her time did: get married and become a homemaker.

But Tarsila do Amaral, one of the most influential figures in Brazilian Modernism, dared to dream big and different. She traveled to Paris, studied art with top modernists, yet she didn’t let foreign cultures influence how she saw art. They inspired her vision to strictly make art embedded in Brazilian culture.

This idea gave birth to one of her most famous paintings, Abaporu (1928).

In case you’ve seen the art and don’t understand the story behind it, sit back and relax; I’ll explain.

Abaporu means “the man who eats.” Yes, a cannibal — but no, we’re not talking about eating humans. Abaporu was a reference to cultural cannibalism. She painted it in 1928 as a birthday gift to her husband at the time, writer Oswald de Andrade.

You know how you make a random post and it unexpectedly goes viral? That was how Tarsila felt about Abaporu; she did not expect it to become a national treasure and a symbol of Brazilian identity in art.

The painting was basically a giant figure with long legs, a tiny head, and a cactus under the blazing sun — an image that depicts Brazil in its beautifully flawed nature, clearly stating that they are not European.

Oswald was so blown away by her painting that he wrote the Anthropophagic Manifesto, a groundbreaking document that pushed back against European artistic rules and set a new direction for Brazilian modernist culture. It was more of a revolution. This became the foundation of the Anthropophagy Movement, one of the most important artistic movements in Brazilian history.

The mission was simple: for Brazil to devour foreign influence and transform it into something uniquely Brazilian.

Abaporu is one of the many iconic works Tarsila produced. She succeeded in rooting herself in Brazilian soil and creating an identity for modern Brazilian art.

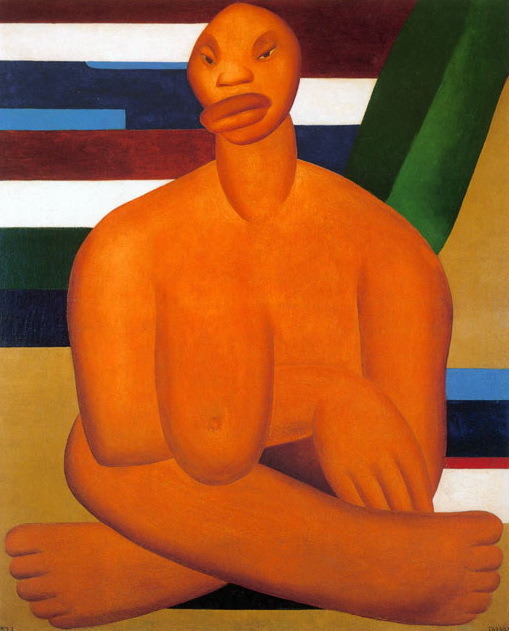

Another of her outstanding paintings, which sparked debate and fueled discussions among many, my favourite, if I must say, “A Negra (1923).”

Painting came naturally to Tarsila. She would paint about her life, the people around her, and things she had seen, mostly with no intention. But people didn’t see “A Negra” that way.

A Negra showed a Black woman sitting on bare ground with exaggerated body proportions. She had large feet and arms, a large breast, a bald head with tiny eyes, and large lips — features often tied to stereotypes of enslaved African women in Brazil.

Although the painting was made years after slavery ended in Brazil, it triggered traumatic colonial memories for many. And for someone from a wealthy background, with Afro-Brazilian and Black women working on her father’s estate, the image didn’t look good on Tarsila.

Although Tarsila never spoke directly on the political or racial impact of the painting, she did say it was based on her memory of an elderly Black woman who used to work on her family’s estate.

An estate which later crashed in 1927 after the economic crisis in Brazil. This forced Tarsila to work and at the time separated from her husband, Oswald who had cheated on her.

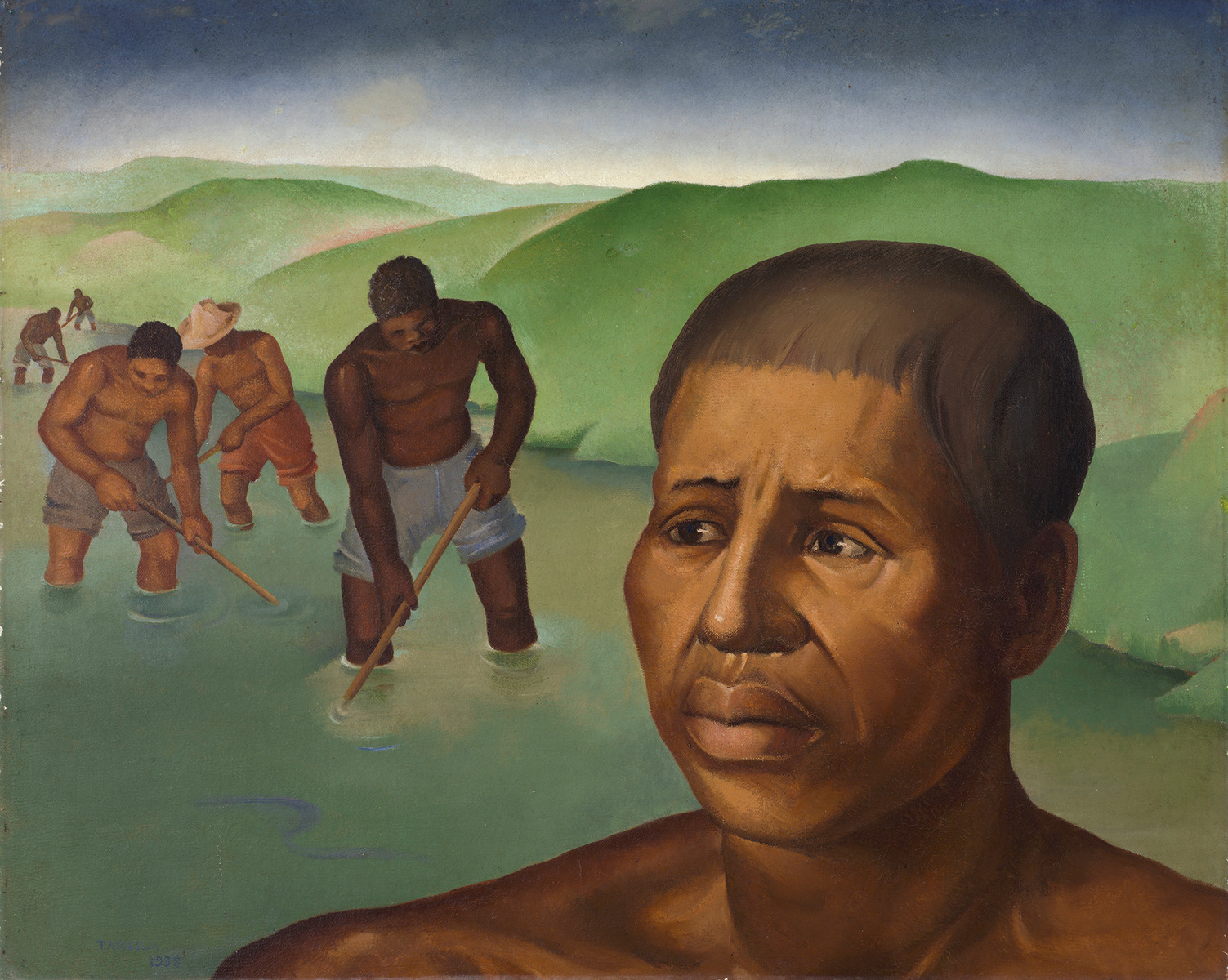

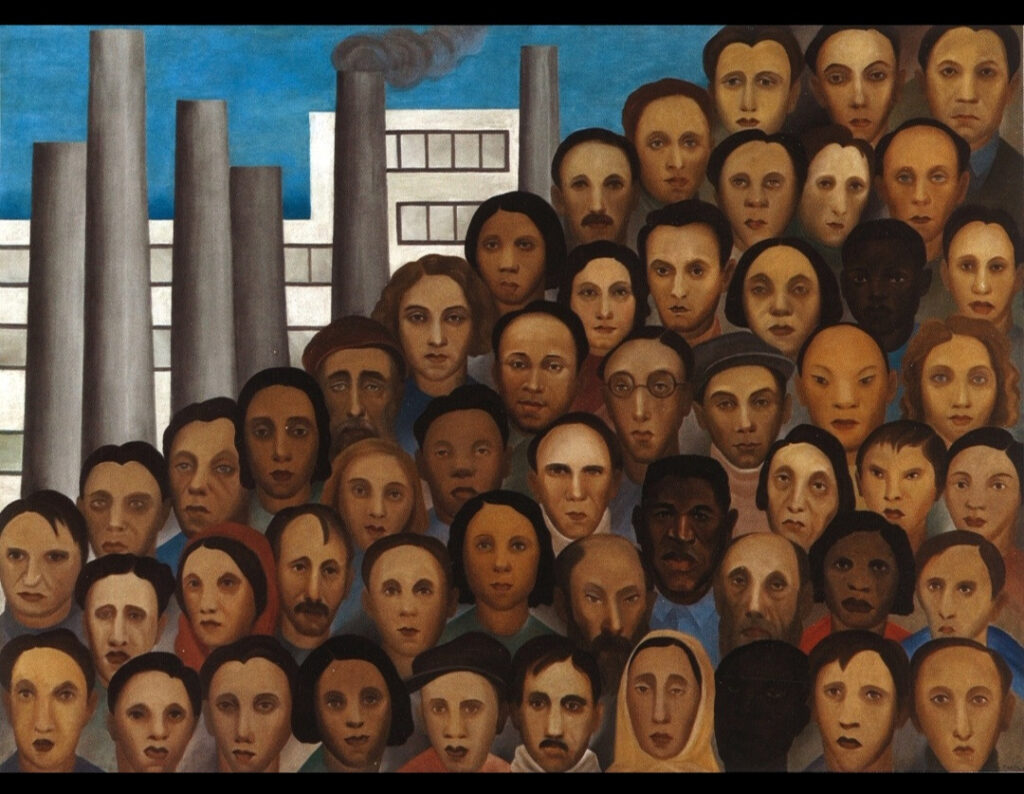

Years later, she traveled to Moscow where she became sensitive to workers’ cause. This inspired her work, Operarios (1933), which depicted a more socially conscious phase of her life. The image shows workers from various racial backgrounds — BIPOC and the harsh reality of industrialization.

Tarsila mirrored every phase of her life through her paintings, she didn’t just create art. She created identity, she created history, and she proved that cultural art in Brazil can thrive anywhere, anytime.